Some notes on the exhibition 'Landmarks' at the

Victoria Art Gallery, Bath, 27 November 2010 -

6 February 2011.

David Tress

David Tress, 'Balloons At Bath', mixed media on paper, 101x110cm, 2009

Jon Benington, in the introduction to the 'Landmarks' show at the Victoria Art Gallery, Bath, writes very perceptively about the relationship of my work to the Romantic tradition. When I left college some thirty five years ago, shrugging off my previous interest in Conceptual Art, I began again to paint, following my 'gut instinct' about the direction that I would take. I had no programme, and it was almost by default that I found, fifteen or twenty years into my life as a painter, that my obsessions coincided with those associated with the Romantic tradition. Thus an obsession with landscape, but not simply as topography: landscape as a sounding board for the emotions and passions - dangerously near to Ruskin's Pathetic Fallacy to be sure, but a good thing to be fearless in the face of the dangerously unfashionable. So, landscape as topography and emotional mirror, and more - landscape as experience of the numinous. Strange to realise that 'numinous', such an essential word, was first used so recently (by Rudolph Otto in 1917), but landscape as a theatre for spiritual experience has been a fundamental of Romanticism from Wordsworth onwards, and in painting makes a link from Turner and Constable, over the intervening century and a half, to Paul Nash and Graham Sutherland.

David Tress, 'Langridge Near Bath', mixed media on paper, 57x77cm, 2009

I found that numerous other of my interests as a painter could be linked to the Romantic tradition. I was drawn to churches, mostly small, old churches both as subjects to paint and as places in which to spend time. I knew, of course, that this subject was fundamental to John Piper's Neo-Romanticism, but took some time to realise that Piper's roots could be found in John Sell Cotman's etchings and water colours of crumbling Norfolk churches and abbey ruins. This interest in old buildings is one characteristic of Romanticism, an awareness of the past in the present, which has been fundamental to the Romantic sensibility from the enjoyment by eighteenth century travelers of 'druidic' remains, to Paul Nash's involvement with standing stones and other Bronze Age and Neolithic sites and megaliths. This links archaeology from the antiquarianism of Stukely, one of the great proto-archaeologists, to Arts and Crafts and Heywood Sumner, and the age of Neo-Romantic photography and painting and some great pioneers of modern archaeology - Alexander Keiller, O G S Crawford, Mortimer Wheeler. All this is well-documented in Kitty Hauser's recent book 'Shadow Sites' (Oxford University Press, 2007).

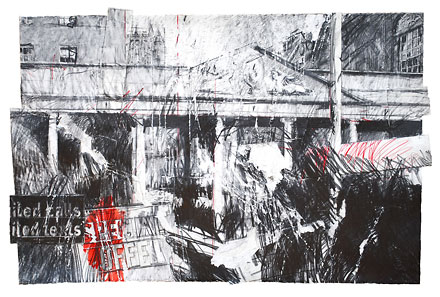

David Tress, 'City Light (Cement Lorry)', mixed media on paper, 77x126cm, 2009

My work doesn't look much like these antecedents. It is after all of the twenty first century, and embraces cement lorries, traffic signs and street advertising as part of the experience of spirit and land, whether rural or urban. As regards influences, clearly I depart from the example of the Neo-Romantics whose language was almost universally informed by the example of Picasso. My early exposure was to the American Abstract Expressionists, themselves having roots in myth and Surrealist subjectivity, and my later influences as a young painter were such as David Bomberg and Joan Eardley.

This awareness of Romanticism and Neo-Romanticism as a living tradition also illuminates and informs my critical awareness. The importance of the Romantic tradition to Modernism - Mondrian's Theosophy, fundamental to his understanding of his own work, and Kandinsky's deep concern for the spiritual are two obvious examples - has been considered in depth by Robert Rosenblum in 'Modern Painting and the Northern Romantic Tradition. Friedrich to Rothko'. The spiritual, however, has been an inconvenience to most recent writers on Modernism (and Postmodernism), and its exclusion has proved necessary to the creation of a form of 'Modernism' that functions as a marketing device too often used in recent decades - most effectively, it has to be said - to sell the negligible to the credulous. In this light the Romantic tradition has teeth! Far from being a dead philosophy, its adoption presents one with a 'billhook' (to borrow a term from that great, if uncertain, Neo-Romantic Geoffrey Grigson) with which to cut through fashionable commonplaces. We must also take seriously the voice of Wyndham Lewis, radical Modernist, Vorticist and fearless commentator, when he supports the young Neo-Romantic artists, as an alternative to what he sees as the superficiality of contemporary culture (in his book of essays published in 1954, 'The Demon of Progress in the Arts').

David Tress, 'Mendip Landscape. Farm And Tumulus', mixed media on paper, 62x108cm, 2009

Viewed in these terms my exhibition 'Landmarks' - correctly seen as in the Romantic tradition - must be looked at a bit more deeply. Almost all the works in the show are about buildings or marks - 'landmarks' - in landscapes which register layers of human activity. 'Palimpsest' is a word used from the 1950s onwards in this regard, and is much used in current academic writing on British Neo-Romantic art of the 1940s and 1950s. Palimpsest meaning, strictly, the faintly visible marks left on medieval manuscripts that have been (almost) erased and re-used, the word is also very effectively employed to describe the multi-layering of marks left by human activity in the landscape over millennia. My paintings and drawings are about various things but include this sense of the past in the present - the landscape as palimpsest. 'Mendip Landscape, Farm and Tumulus' has as its subject farm buildings, walls, telegraph poles and a pre-historic mound which span some 2500 years. Small country churches such as Langridge or Limpley Stoke show evidence in their fabric of the original Anglo-Saxon or Norman buildings - the building itself functioning as palimpsest. 'Balloons at Bath' shows the western front of Bath Abbey, its exceptionally late Gothic façade being interrupted by children's balloons in the foreground. The Abbey stands on the approximate site of the Roman 'Tholos' of two thousand years ago, a Greek name used to describe the small round temple that was part of the Roman baths and temple complex. Sulis Minerva, the Romano-British deity to whom the hot spring was dedicated, characterizes the link of spirit and land. The spring and baths were practical, functional and also spiritual, and the temple complex was integrated with the practical function of the baths. Today the religious no longer has this intimate association with the land; the Abbey is now an entity discreet from the Baths. In the drawing 'Bath (Passing Trade)' the view is of the shopping street next to the Abbey - the street is some meters above the buried precincts of the Roman Temple - to follow the theme of Greek names we might call it the 'temenos' - but today's shopping street is more than physically isolated from that relationship of spirit and land.

David Tress, 'Bath (Passing Trade)', graphite on paper, 102x162cm, 2009

Books referred to in the text:

'The Demon of Progress in the Arts', Methuen, 1954.

'Modern Painting and the Northern Romantic Tradition. Friedrich to Rothko', Icon, 1975.

Other books dealing with the continuing Romantic (Neo-Romantic) tradition:

'Romantic Moderns. English Writers, Artists and the Imagination from Virginia Woolf to John Piper', Thames and Hudson, 2010.

'A Paradise Lost. The Neo-Romantic Imagination in Britain 1935-55', exhibition catalogue pub. by Lund Humphries in association with the Barbican Gallery, 1987.

'British Romantic Art and the Second World War', Macmillan, 1991.

'This Enchanted Isle. The Neo-Romantic Vision From William Blake To The New Visionaries', Gothic Image, 2000

| Home | Gallery | Biography | Reviews | Exhibitions | Videos |